Diplomats and Dissent: The case of Sir Dadiba Dalal

|

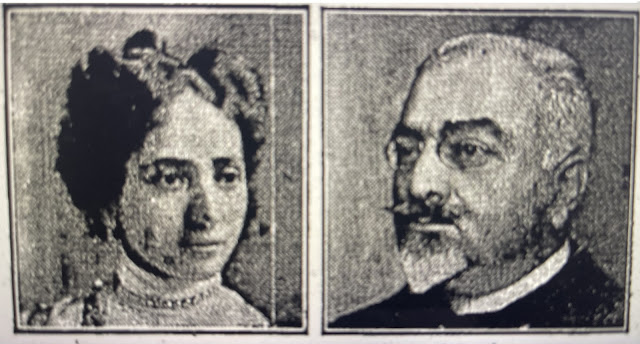

| Sir Dadiba and Lady Dalal |

In my research on colonial Bombay's merchants and industrialists, I came across Sir Dadiba Merwanjee Dalal. In the current time he is clearly not the most famous Parsi with the surname Dalal. That tag would easily go to someone like Sir Ardeshir Dalal, an ICS officer, senior Tata executive, and one of the signatories to the Bombay Plan. But what is the connection between Akhilesh Mishra and Sir Dadiba Dalal? Well, Sir Dadiba was the first Indian to be appointed the Indian High Commissioner to the UK and was known to fiercely speak his mind, especially if it meant protecting the interest of India's trade and economy.

Although Dadiba Dalal's diplomatic appointment remains a cornerstone, it was his dissenting opinion as part of an important committee for which he is much better known. "In my opinion the duty charged on silver imported into India is closely connected with the currency policy, and is calculated to deter the economic advancement of the people of India." Thus wrote Dalal in his minority (dissenting) report as a member of the Committee on Indian Exchange and Currency in 1919. The committee was formed after the end of World War I and included senior officials involved in financial and currency management of British India. Dalal was the sole Indian on the committee and did not agree with the recommendations of ten of his (British) colleagues.

Dalal was the head of the famous Messrs Merwanjee & Byramjee, a firm which was sole broker to Bombay Port Trust, Bank of Bengal and Bombay Municipal Corporation. Dalal also made a name for himself due to his regular writings on financial and trade matters in newspapers, including The Economist. He was inducted in the committee because he had strong views on the economy and was a constant critic of the unnecessary and manipulative interferences by India Office into the working of the Government of India. In colonial times, the India Office was based in London working under the Secretary of State for India, while the Government of India was headed by the Viceroy.

Dalal strongly felt that India had received a raw deal by Britain despite the immense help London got from the subcontinent. India supplied men and materials for the War, but currency arrangements set by London was causing immense hardships to the great masses of India. Essentially, Dalal opposed the recommendation of the committee to raise the standard rate of rupee exchange from 1s 4d sterling at which it had stood for 20 years to 2s gold. Dalal's stand was proved correct after the government corrected the ratio by fixing it at 1s 6d sterling, but not before crores of rupees was spent.* Dalal also regularly argued that it was wrong to believe that large scale hoarding of gold took place in India.

Dalal became the first Indian to be the Indian High Commissioner to the UK when he took charge in April 1923. The need for the position arose after it was felt that the Secretary of State for India, positioned in London, could not do an effective, remunerative job for certain aspects for which an Indian High Commissioner was needed. The first incumbent was Sir William Meyer, who died while in the role. For a brief period an ICS officer Sir Joseph William Bhore (also an Indian) temporarily took charge.

It would be fascinating to discover the discussions that led to Dalal being chosen for the role. The process of 'Indianizing' the services in India which had begun meant that Dalal was an ideal candidate. As said earlier, Dalal was not really fond of interventions by the Secretary of State in Indian affairs undercutting Government of India. What better person than Dalal to take on a position which was established to have a GoI appointee in London. The high commissioner was directly responsible to the GoI and not Secretary of State.

Unfortunately, Dalal lasted only 18 months in the position and resigned in September 1924. In retrospect it must have been a embarrassing position for GOI to have Dalal resign so quickly. Bad health and other polite excuses were offered, but it was clear that he was not suited to the life of a civil servant. As a sharp and successful broker, dealing in stocks and bullion, Dalal was used to oral agreements and quick decisions, not really the hallmarks of a civil servant of that era. He was ably supported by his wife who had accompanied him to London and both attended the usual circuit of parties and diplomatic events. After his resignation, Dalal lived mostly in France where he died in March 1941 at the age of 70.

Dalal's father Merwanjee Rustomjee Dalal had similarly passed away in London, away from India, in 1899. Merwanjee Dalal had come to London due to ill health of one of his children. After his death Dadiba - who was the eldest son - took over the reigns of the hugely successful brokerage partnership firm. In fact so respected was Merwanjee, that hardly any cotton mill owner or bank official would have not sought his advice on important issues. Merwanjee and his school friend Byramjee had come together to establish Messrs Merwanjee & Byramjee which brought incredible fame and wealth to their families.

It was also a scenario of son following in the father's footsteps. While in England, Merwanjee gave evidence to Sir Henry Fowler's commission on currency. Twenty years later his son Dadiba Dalal gave a dissenting opinion as part of an equally important committee. Dalal wrote a fairly detailed dissenting opinion which acquired a life of its own. Banking and financial companies started using portions of his comments to show the huge scope for advancement of banks in India. Dalal had stated that lack of modern banking facilities had led to "money lying dormant in endless small hoards" and that India represented a vast virgin field for the development and expansion of banking.

At the risk of sounding politically incorrect, it won't be wrong to say that exploitative and extractive colonial regimes knew that on serious issues dissent was good. Elsewhere I have written about two other industrial magnates Sir Purshottamdas Thakurdas and Sir Ibrahim Rahimtoola who did much to further the interest of Indian trade and commerce even if it meant voicing opinions not to the liking of the British administration.

In Dadiba Dalal's case not only was he proved right, he also got a prized diplomatic appointment. That he didn't last long in London was perhaps another indication of his independent mind.

*Dalal represented the Bombay school which believed that the ratio should be 1s 4d and not 1s 6d. The demand for 1s 4d was led by individuals like Sir Purhottamdas Thakurdas, Sir Victor Sassoon, Jamnadas Dwarkadas and others which led to the formation of the Indian Currency League.

Comments

Post a Comment